Sacred Time

Depending on your faith, today is either the most spiritually significant moment of the year . . . or the day when all those chocolate and marshmallow bunnies go on sale.

We are going to spend a few words reviewing what Easter Sunday is all about within the context of the Christian tradition. Then we’re going to try to explain why we think it is relevant to anyone interested in magic and the supernatural, regardless of faith.

Just to be clear, what follows is neither an endorsement nor a condemnation of one particular religious practice. Our intent is primarily to use the example of well known religious festival to illustrate the concept of Sacred Time.

Holy Week

Theologically speaking, it is Easter, not Christmas, that is the highest holy day in Latinized Christianity. Furthermore, Easter can’t really be taken by itself. It is the celebratory climax of an eight-day ritual known as Holy Week. For anyone who didn’t go to Sunday School, here is the short version.

Holy Week begins on Palm Sunday. This celebrates the day when the working-class Jewish prophet, Jesus, was said to have ridden into Jerusalem on a donkey. The common Jewish people of the city, whose ancestral home was occupied by Roman Imperial colonizers, celebrated by scattering their clothes and tree branches on the ground.

Predictably, neither the Roman government, nor the Jewish leadership who had reached an accommodation with said Romans, were terribly happy at the arrival of this messianic figure. They dithered and fretted for several days, but by Thursday they had come up with a plan. They would bribe one of the apostles, Judas, to betray Jesus after a meal that would become The Last Supper. This is Maundy, or Holy, Thursday.

A day of ridicule and torture followed, and concluded with Jesus being brutally executed by crucifixion on a hill outside the city walls called Golgotha. The sequential events from formal condemnation to death are sometimes referred to as The Stations of the Cross, but the day as a whole is commemorated as Good Friday.

He was placed in a tomb and remained there, dead, until Sunday. At that point, Mary Magdalene arrived to discover the tomb empty and the humble Carpenter returned to life. He brought news of a New Covenant whereby the faithful would have their sins forgiven and be given life after death. This is Easter.

If you are a member of the Christian faith this revelation is the core tenet of your belief. The various Christian sects may disagree, sometimes bloodily, on the details. But at its most fundamental, Christianity is the affirmation of the events described during this Holy Week, and the promise that adherence to Christ’s teaching will lead to the immortality promised at the Easter resurrection.

What are Sacred Time and the Eternal Return?

While Holy Week is obviously important to Christians as a celebration of their most important spiritual belief, it is also relevant to anyone more generally interested in faith and the supernatural. For most people in the Western world, it is the most familiar example of the linked concepts of Sacred Time and the Eternal Return.

For these purposes, Profane Time is the time that we normally exist in and think of as linear and progressive. (Note the “profane” here doesn’t mean “bad.” It is simply time that does not have a mythological component and is not “sacred.”) Now it is 2022. Next year it will be 2023, and the only way to travel back in time will be through memory and photographs. We move inexorably forward, afloat on an unceasing river until we sink and are lost to those who continue forward. That it just how Profane Time works.

Sacred Time, however, is a different creature entirely. Holy Week doesn’t exist in 2022, not really. Not any more than it will exist in 2023, or existed in 1950, or 1250. It exists in anno domini 33 (or near enough depending on what medieval monk’s math you want to use). Holy Week is a celebration of a moment that has become unstuck in time. Or, perhaps, a moment that simply can’t be mapped using Profane Time any more than you can say what collection of elementary particles makes “love” or what the waveform of “grief” is.

The linked idea is that of the Eternal Return, the belief that we have the ability to step out of Profane Time and into Sacred Time through the celebration of timeless Holy moments. Staid Christian businessmen in gray suits chanting and singing in celebration Jesus’s resurrection exist in Profane Time at whatever moment their Rolex watches state. However, their spirits have time travelled two thousand years into the past.

Contemporary Jews celebrating the feast of Passover slide out of today and into the moment when a humbled Pharaoh granted their ancient ancestors their freedom. Americans routinely inhabit their timeless mythic spaces where cannons explode over besieged forts, where Union troops apply the Emancipation Proclamation to Texas slaves, and even where pilgrims and “Indians” happily share turkey. No one said that the mythic spaces of Sacred Time need to be authentic in terms of historical accuracy. Such accuracy is a bound of Profane Time.

It is generally assumed that this concept of Sacred Time was easier for pre-modern people to fathom. After all, the patterns of life were probably much more stable from year to year and from generation to generation. A ninth century medieval peasant could easily have seen the world as a timeless place in which ancient Jerusalem appeared similar to the few square miles of Aquitaine in which she would live her entire life.

At first glance, it seems a more alien idea for contemporary people, what with the blistering pace of technological and social change. However, we believe that our entertainment provides a helpful metaphor. We routinely watch films in which now dead actors populate now radically different vistas, and yet we experience the existence of those fictional moments as vividly as we might years or decades into the past or future. We recognize in such viewing that Profane Time need not bound our mental space. The act of watching Ghostbusters might not quite be entering Sacred Time, but it is something adjacent.

On Magic and the Eternal Return

Where a viewing of Ghostbusters and the celebration of Sacred Time differ is in the agency of the participant. This is perhaps less obvious in many contemporary religious rituals in which a largely passive congregation mostly just watches robed priests do things. But it is clearer in something as mundane as the above referenced Thanksgiving dinner. Families gather together to ritually consume the bounty of our successful subjugation of the continent while acting out a mythic narrative of giving amorphous thanks to some combination of God, the government, and freedom for letting us be the only half of the pilgrim/native duo still celebrating.

This brings us to magic, here defined as using a combination of imagination, desire, and ritual to enact change upon the material world. Generally, the things we think we care about are in the profane world. We want to be and feel certain ways. We want stuff. We want other people behave how we’d like. Again, “profane” here doesn’t mean bad or irreverent. (We, personally, routinely crave a magic that would make people less inclined to hate and murder each other.) It just means of the material, rather than the supernatural, realm.

In celebrating Holy Week, in bringing people into Sacred Time to celebrate a mythic moment from two millennia ago together, the faithful aren’t just playing a fun game of temporal projection. They are performing a powerful magic ritual, fueled by the congregation’s imagination, to impact their behavior in the mundane world. The effectiveness of all such rituals will vary with the participants, the particulars of the ritual, and with the variable input of the Divine. But there are at least some circumstances in which, after traveling through time back to Golgotha, those parishioners will go out and act far differently than they would have before they partook in this bit of magic.

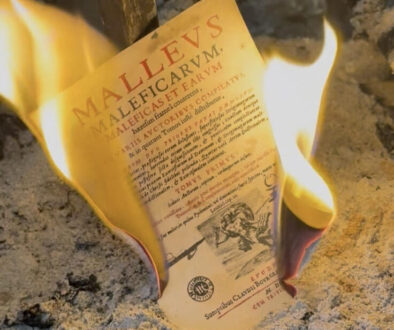

The events in Sacred Time to which we travel when we make the Eternal Return to mythic origin stories are thus, strangely, not fixed in either content or focus. We don’t need to imagine how a subtle change in focus during the Sacred Time could influence those who journey there, profane history tells us. Routinely during the Middle Ages, enthusiastic celebrants would focus on the apparent perfidy of both Judas and the Jewish leaders who allied with the Romans. Ignoring the fact that Jesus was also Jewish, these faithful Christians would become so enraged by the death of their timeless savior that they would celebrate Good Friday with the murder of their Jewish neighbors.

More dramatic still is the fact that not all Eternal Returns need to be made. We may choose to visit some Sacred Times and not others. In other words, the Sacred and the Profane are in a constant dialogue, influencing one another in an eternal magical dance that may see either go extinct. For thousands of years the Ancient Egyptians made an Eternal Return to a Sacred Time that in turn moved their civilization to create the vast necropolitan monuments that far outlasted their creators. Did the shared timeless stories of these people change? Or did the people and their environment change? The answer, of course, is both.

Where Does Sacred Time Go?

A masterful wizard, a gifted propagandist, and a talented advertising executive will all tell you the same thing using different language. You change the physical world by changing the stories that people believe, by sending them to a different Sacred Time. The bigger the change you want to make, the more fundamentally you have to alter where people go when they make their Eternal Return. Where the wizard (or a priest) might differ from the others is in their belief in the independent existence of the things from Sacred Time.

To the person only interested in manipulation, the story is just a tool for control. Tweak the myth and you can influence the people who believe it. If all you want to do is sell more perfume, then maybe you just need a few images and words to fleetingly send a would-be customer to a Sacred Time in which they were younger and prettier. If you want to work people up into a revolutionary fervor, maybe you need a torchlit rally in which participants luxuriate in nostalgia for a timeless great nation that was ruined by whomever you’d like them to hate today. The last centuries have certainly taught us that toxic myths can make people do monstrous things. And maybe that is all there is. Maybe it is all just media studies and neuroscience.

For what it’s worth, we believe that all that faith goes somewhere, all those visits to Sacred Time carve deep grooves into collective mental spaces that humans don’t have good words for. It is all more complicated than effective slogans and words and power. Maybe that faith merely goes into culture, where it just keeps going in an endless thrumming cycle of communication and exchange so vast that it is incomprehensible. But if so, then “culture” becomes a word so big it might as well be magic.

Most people who care about the supernatural, though, will tell you there is more to it than that. A billion celebrations of Holy Week spread across nearly two thousand years have left a mark and have shaped a spiritual landscape for everyone, faithful or no. Only the deeply reckless will call up a spirit between Good Friday and Easter when the protective God a billion people pray to is in His tomb. And the most heretical of sorcerers will acknowledge the benevolent powers of salt gathered from a crossroads at dawn on Easter morning. The Sacred Time may only exist because we want to go there, but that doesn’t mean we don’t bring some of us back with us.

All of which is a reminder to tell good stories, and to tell stories of good, for while we may make our myths, ultimately our myths make us.

Happy Easter everyone, whether it is a holy day, or just one for eating chocolate bunnies.