The Hierophant

We were recently had a conversation with a friend about a particular Tarot card, and about our name.

It was a conversation held at some remove in space and discontinuous in time. Perhaps because of those separations, the dialogue helped us to put together some thoughts about an oft-maligned card, The Hierophant.

Our name owes more to the seminal work of Mircea Elliade, The Sacred and the Profane. Elliade’s personal life and politics were deeply problematic, but his short and powerful book remains a foundational text in religious studies curricula. He described the ineffable process by which the sacred (hieros in Greek) reveals (phainein) itself as “hierophany.” It is a moment when the material world becomes something more than base matter. It is a difficult concept to explain, but one familiar to anyone who has looked at a sunrise and felt in it something more than can be explained by high energy physics.

Though our hierophany is more about revelation, we obviously were aware of the more familiar variant of the word as found in almost every tarot deck. Historically, the hierophant was the keeper of sacred mysteries in Ancient Greece. In large part as the result of the Tarot, it has become synonymous with “high priest” in general, and in particular with the Pope of the Roman Catholic faith.

The most familiar contemporary reading of The Hierophant focuses on the card as an embodiment of conservatism and conformity. Phrases like “socially approved, safe” and “obedient” make frequent appearances. While there are no “good” or “bad” Tarot cards, it nonetheless has a decidedly negative reputation. It is the scold of the deck.

We believe that this is an unfortunate consequence of the iconography of the card. That iconography, of an enthroned Pope, speaks to the medieval and renaissance origins of the Tarot. The originators of these cards would not have had a visual language to deal with the concept of hierophany other than that of the Church. Unfortunately, that same Church has been in sometimes lethal tension with all things “occult.”

As a result, we have a card representing sacred topics with a visual language that is off-putting to many of the people most drawn to magical practice. This isn’t to blame or absolve said Church. We’re just arguing that this card has become linked to the procrustean features of authoritarian establishment religion because of its depiction of what could just as easily be described as a “high priest.”

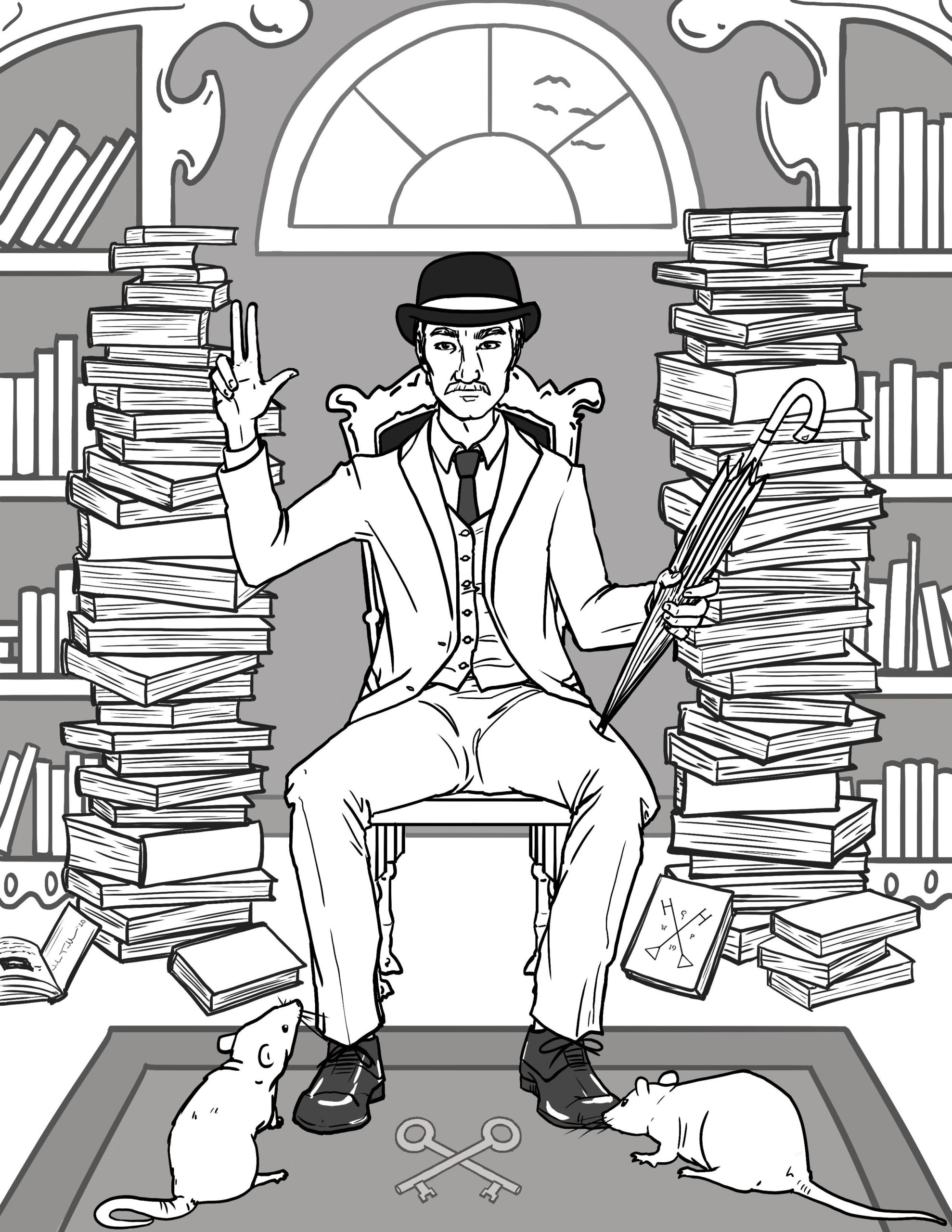

We believe that the pair of crossed keys at his feet are more important than the apostolic raiment of the high priest. These are a representation of the keys to heaven that in the Christian faith were entrusted to St. Peter by the Christ. They are flanked by a pair of petitioners, presumably seeking the wisdom and blessings of the high priest, and guidance toward their own spiritual salvation.

This construction emphasizes the role of The Hierophant as mediator between the sacred and the divine. Like every other priest, shaman, or spiritual guide, he serves as shepherd guiding a flock safely between this world and all others. For some that may in fact mean mortification of the flesh and social conformity, but for others it may mean something radically different. The Hierophant is not advising one to be the same as anyone else. It is speaking to an accord between one’s temporal and spiritual lives, so that the material world might gain access to the divine.

The history of the meaning of tarot cards is an occult science in its own right and as with any living document (for any number of values of “living”) the most accepted meaning of any given card is constantly in flux. For instance, consider the 1910 The Tarot of the Bohemians, which is arguably the book that brought the Tarot into the mainstream of occult practice. In this book’s section on The Hierophant there is nothing about conformity or obedience. Our intent here is not to contradict or disparage any particular interpretation of The Hierophant, but merely to offer another possibility.

Furthermore, just to be clear, our humble hierophany is not anything so grand as a high priest of any faith. But we do like to think we’re part of a tradition of balancing the secular and the spiritual and of finding magic in the material world. More importantly, we want to make it clear (in case it isn’t obvious from the fact that we are stewards of a magic shop) that our name wasn’t selected to support any ideas of forced conformity.